Is 1967 the most stylish year ever?

In my last — aka first — style | sound post I wrote about Bill Evans’ 1967 jazz album A Simple Matter of Conviction.

Now let’s turn our attention to a different coast and different genre, but same year. Where Evans’ Conviction was recorded in New Jersey and has the layered nuance of the New York City skyline, Brenton Wood’s Oogum Boogum is 100% Los Angeles — candy-colored like an LA sunset or Hollywood backdrop.

Wood himself was born Alfred Smith in Shreveport, Louisiana. His family journeyed west, to San Pedro and then Compton, when Wood was a child. I can’t say for sure, but I’d guess the move was part of a migration many Black Americans were making at the time in order to escape the blatantly racist south — not that Southern California was necessarily much better — and to find work in the run up to World War II, where the docks and factories of California held greater opportunity.

Where Bill Evans provides emotionally and musically complex jazz, Brenton Wood offers a sort of bubblegum soul confection. If Evans is a smoky cocktail, Wood is a cherry — make that cheery — popsicle.

That sounds like a criticism. And indeed it’s one that many music critics have levied at Wood over the years. But from me it’s a high compliment.

Sometimes — probably often — you want a dessert, you want a simple pleasure, you want a sweet treat, you want to feel yourself move and groove and float and sway. And that’s exactly what Oogum Boogum delivers.

It’s a ride in a convertible with the top down on a bright, sunny day. It’s a walk in the park with your hand clasped in your sweetheart’s. It’s a piece of delightfully simple milk chocolate in a swirling, moody sea of 77% cacao.

And it’s one of my favorite album covers of all time.

a bit of background

The title track was released as a single first and the album pumped out shortly after to capitalize on the single’s success. It’s probably best known now for being featured in an over-abundance of films, TV, and commercials — including Almost Famous and Don’t Worry Darling. The only other song off the record to chart was “Gimme Little Sign” — a similarly soulful confection as “Oogum Boogum Song.”

“Oogum Boogum Song” tends to overshadow the rest of the album, but many other tracks are gems as well — like “Best Thing I Ever Had,” “I Like The Way You Love Me,” and “I’m The One Who Knows.”

In the classic soul music tradition there are generally two kinds of vocalists: crooners and shouters. Both emerge out of Black gospel and choir music. The easiest way to distinguish between the two is to point to a pair of their most famous practitioners: Sam Cooke and Otis Redding.

Cooke is the ultimate crooner, with a smooth delivery matched only by his smooth productions and smooth backing. You could listen to any given Cooke track — “You Send Me” for example — and hear what I mean. Cooke — and by extension other crooners — are satiny and silky in their vocalizations. They sit flush with the music rather than exaggerating it.

Otis Redding is grittier, punchier, harder-hitting. He quite literally shouts, pushing the words out with force and intensity. The way he performs at the iconic Monterey Rey Pop Festival (held in guess what year? 1967!) bolsters this image. He’s raucous energy personified.

Both Cooke’s tragic and mysterious shooting in LA and Redding’s unfortunate and unforeseen death in a plane crash — just a few months after his Monterey performance — leave us with a pair of music history’s greatest “what ifs.”

But back to Brenton Wood.

His vocals are lilting, gentle, almost effortless. They glide rather than push. Textbook crooner. The instrumentation and arrangements are fairly straightforward. They don’t pop, with exception on the track “Psychotic Reaction,” but they are pop.

But I think to leave it there does a disservice to Wood and to Oogum Boogum. Sometimes Wood lets his voice rise into a falsetto — a la Frankie Lymon — and he accentuates a slapping snare, a jangly guitar, or a bopping piano. His little vocal inflections — assorted ‘oomphs’ and ‘oooohs’ — exaggerate and embellish the lyrics and music in a way that refreshes, like a cold drink on a hot day.

My favorite track is the second charter — “Gimme Little Sign.” Unlike “Oogum Boogum,” “Gimme Little Sign” is less cute and more cool. It’s chewier — with more texture and bite than the (delicious) empty calories of the title song. The drummer runs a bit more wild and Wood cuts a bit looser as he sings.

Going into the chorus there’s an itty bitty break — a small precipice — as if the song is ready to spin out.

“There’s just one thing that you should dooo…”

And then Wood and the band reel it in fast, so fast you almost don’t notice it.

“Just gimme some kind of sign girl”

The fact that Wood contributed so much of the writing means the record isn’t composed of former soul hits or tried-and-true staples. These are new riffs on familiar ideas about love, lust, and lingering looks. It’s a stab at originality, an attempt to fashion new classics.

From a sociopolitical perspective, the kind of adolescent innocence Oogum Boogum evokes was likely hard to square with the rising escalation in the Vietnam Conflict and the fact that those formerly innocent teens were now seeing their brothers and friends, if not themselves, being shipped off to fight.

But Oogum Boogum is also more overtly naughty — in a good way — than prior soul crooners’ outputs. The narrator of the title song lists outfit after outfit that his sweetheart wears and the ways those outfits excite him.

“When you wear your bell bottom pants

I just stand there in a trance

I can't move, you're in the groove

Would you believe, little girl, that I am crazy 'bout you

Now go on with your bad self”

It’s not quite explicit, but it’s pretty damn close. And it’s also a celebration of attire unlike any other in music, which is — pardon the pun — music to this clothing-lover’s ears.

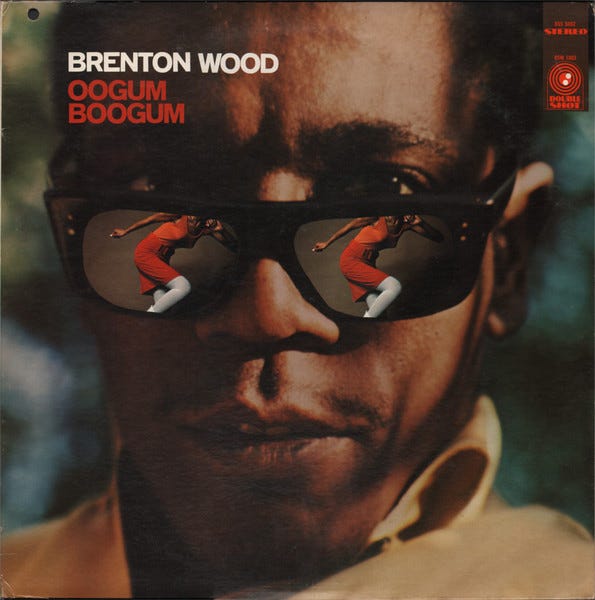

Now to discuss that album cover (pictured above).

It features Wood in a pair of chunky, black sunglasses, a style that remains popular to this day. Wood gazes directly into the camera, thus gazing directly at us, his audience.

The glasses sit midway on his nose so we can see into his eyes. His lips are slightly parted and the shadow of a neat pencil mustache is visible. He’s undoubtedly good-looking, with a square jaw, defined features, and an intense stare.

And what a stare: Wood seems bewitched, entranced, struck. His gaze filled with unsubtle longing, as if he is propositioning us, his prospective audience, daring us.

Basically, it’s a performance of arousal, a performance of the stereotypical image our culture associates with one individual eyeing another. Sunglasses pulled down, eyes undressing, seeing a person as an object of desire.

The kicker is of course that what’s reflected in Wood’s glasses is not the camera, not his audience, but twin images of the same woman. She wears a stylish outfit — contrasting shades of orange. She’s caught mid-movement, mid-flex, mid-gyration —her muscles clearly defined in her arms, shoulders, and collarbone.

The fact that her head is cut off in the “reflections” indicates that Wood is seeing her as just such an object of desire. The fact that she is so clearly dancing seems to me to suggest that she is almost an idealized vision for Wood, a fantasy dream of what he hopes his music will do for listeners: get them moving, get them grooving.

The reality is that the cover photo is a rendering of the title song. Wood “can’t move” because the woman in question is “casting spells” on him. Knowing the subject of the title song, knowing its lyrics and meaning, what seems at first to be a simple objectification becomes so much more.

In the way that sex workers often say they hold the power in the relationship with their clients (when conducted in safe environments with proper regulation and care), the dancing woman holds the power in her relationship to Wood. She owns him, even though she is the one held by his stare. Captive becomes captivator.

What is truly fascinating to me is the way the album cover centers Wood and not the woman. Plenty of covers — especially from the mid 20th century — feature women dancing, women in various states of undress, or women sultrily gazing into the camera. This is because the target market for these records was assumed to be men and music — like all popular art — is a commodity before it’s anything else.

It would have been par for the course to make the album cover just an image of the woman dancing.

Instead, Wood is the one gazing sultrily into the camera. He’s the one we can’t take our eyes off of. He’s the one we objectify. He becomes the centerpiece. The photo makes us look at Wood the way Wood looks at the woman. We become just as bewitched, just as hypnotized, as he does.

Enjoying the style | sound series ♥️